Qingming, 清明 — Clear and Bright

“清明時節雨紛紛”

—During the Festival of Qing Ming drizzling is the rain. (Du Mu, 杜牧)

Qingming Festival

The Qingming Festival (清明節), alternatively called as Tomb-Sweeping Day (掃墳節) is an ancient Chinese tradition with a history of more than 2500 years. The first day of the festival falls on the 1st day of the 5th solar term of the traditional Chinese lunisolar calendar. This day is the 15th day of the Spring Equinox which means it is either the 5th or the 4th (in bissextiles) of April.

Each solar term can be further divided into three pentads (候, hou) which makes:

- the first pentad (初候, chuhou),

- the second pentad (次候, cihou)

- and the last pentad (末候, mohou).

In China every pentad has a sort of title:

- the first pentad of Qingming is when ‘the paulownia begins to bloom’ (桐始華),

- the second is when the ‘voles transform into quails’ (田鼠化為鴽)

- and the third is when ‘rainbows begin to appear’ (虹始見).

The festival originates from Hanshi (寒食節, Cold Food Festival) during which folks remembered Jie Zhitui, a nobleman of Jin (Shanxi) who lived during the Spring and Autumn Period. This nobleman was loyal to Prince Chong’er and followed him even to exile. It is said that one time he even cut out meat from his tights to feed his lord. Upon returning from exile, the duke forgot about Jie, who, humiliated as he was, decided to retire and move into the forests with his mother. Time slipped by and one day the prince remembered his old companion and he immediately set off to find him, alas in vain, the onetime nobleman was reluctant to leave the forest. The prince then had the forest set fire so that his hiding companion would have to surrender. However, after the fire cooled down, they found but dead bodies, and the prince was overcome with remorse and erected a temple in his honor. In memoriam of Jie Zhitui, people started to feast and eat but uncooked meals and set no fire around the day of his departure. As time went by it also became the period when families went out to the tombs of their beloved ones and cleared off the dust of the old year. And so begin the tradition of tomb-sweeping.

Kite running is a favourable outdoor activity in China during Qingming

Kite running is a favourable outdoor activity in China during Qingming

Celebrating Qingming

There are numerous common activities for Qingming Festival. The most common ones are tomb cleaning (hence the name, Tomb-Sweeping Day), spring outings, and kite flying. People also participate in different kinds of sports to celebrate the arrival of spring.

The tradition of tomb sweeping has been legislated by the emperors who erected magnificent gravestones and monuments in every dynasty. For over 5000 years, the Chinese imperials, nobility, merchants, and peasantry all gathered together to commemorate their beloved departed ones and to perform Confucian filial piety by tomb-sweeping and making offerings.

Qingming is many times referred to as Taqing (踏青, tread green), which loosely translates to spring outing. This is a time when people spend time outdoors enjoying the spring and taking pleasure in the fresh blossoms. Taqing marks the beginning of a new period when the world turns green and life returns.

Sazi (撒子), or hanji (寒具), a traditional, crispy Qingming food

Sazi (撒子), or hanji (寒具), a traditional, crispy Qingming food

During the Festival, some people wear tender willow branches attached to their clothes and also decorate gates and front doors with them. It is said that this custom helps to ward off malicious spirits. The willow bears miraculous power in the Buddhist tradition. In many depictions, Guanyin (觀音), the Goddess of Mercy is shown seated on a cliff, attributed with a willow branch.

Similar to mooncakes that are consumed during the Chinese New Year Festival, there are traditional foods of Qingming as well. Sazi (撒子), or hanju (寒具, cold food) are crispy, fried golden strands of dough, made of rice flour, eggs, sesame, onion, and salt. Sometimes it is also referred to as ‘shiba pan’ (十八盘, 18 twists). People would eat it before warm meals or while drinking tea.

Fresh buds and tender leaves before Qingming, the material for sweet first flush teas.

Fresh buds and tender leaves before Qingming, the material for sweet first flush teas.

Qingming and tea

Every year as Spring dawns Chinese people enthusiastically await the spring tea harvest to commence. In the early days of spring, when the first buds broke, the newly unfolding tea leaves are delicate and gentle, and the buds contain more sugar, amino acids, and other flavor compounds than at any other time of the year. These teas are immensely praised and highly prised for their exquisite, lightsome, and sweet taste.

Early springtime teas are often called first flush teas. The term traditionally refers to those green teas that are plucked before Qingming, therefore they are also called ‘mingqian’ (明前, before (Qing)ming). Teas that are harvested right after Qingming (5th of April) are called ‘guyu’ (谷雨, grain rain) which is the next Chinese solar term (20th of April). And there is a third period, starting with the 5th of May, called ‘lixia’ (立夏, start of summer). As we advance into summer, so goes down the value and quality of teas. A mingqian tea can worth up to 100 times more than one harvested in mid-May.

Of course, this is a highly market-oriented phenomenon and cannot be applied to all kinds of teas. For instance, at the time of Qingming there is not a single tea bush sprouting up north, and the tea gardens of Yunnan are well into the harvest season.

In any case, with the Chinese, we too are eagerly waiting to taste the first infusions of the new harvest. Every year we order from Jin Chiyabari’s first flush Himalayan Spring. We very much like its crispy, citrus-like taste that melts with mellow notes of nuts and freshly-baked bread.

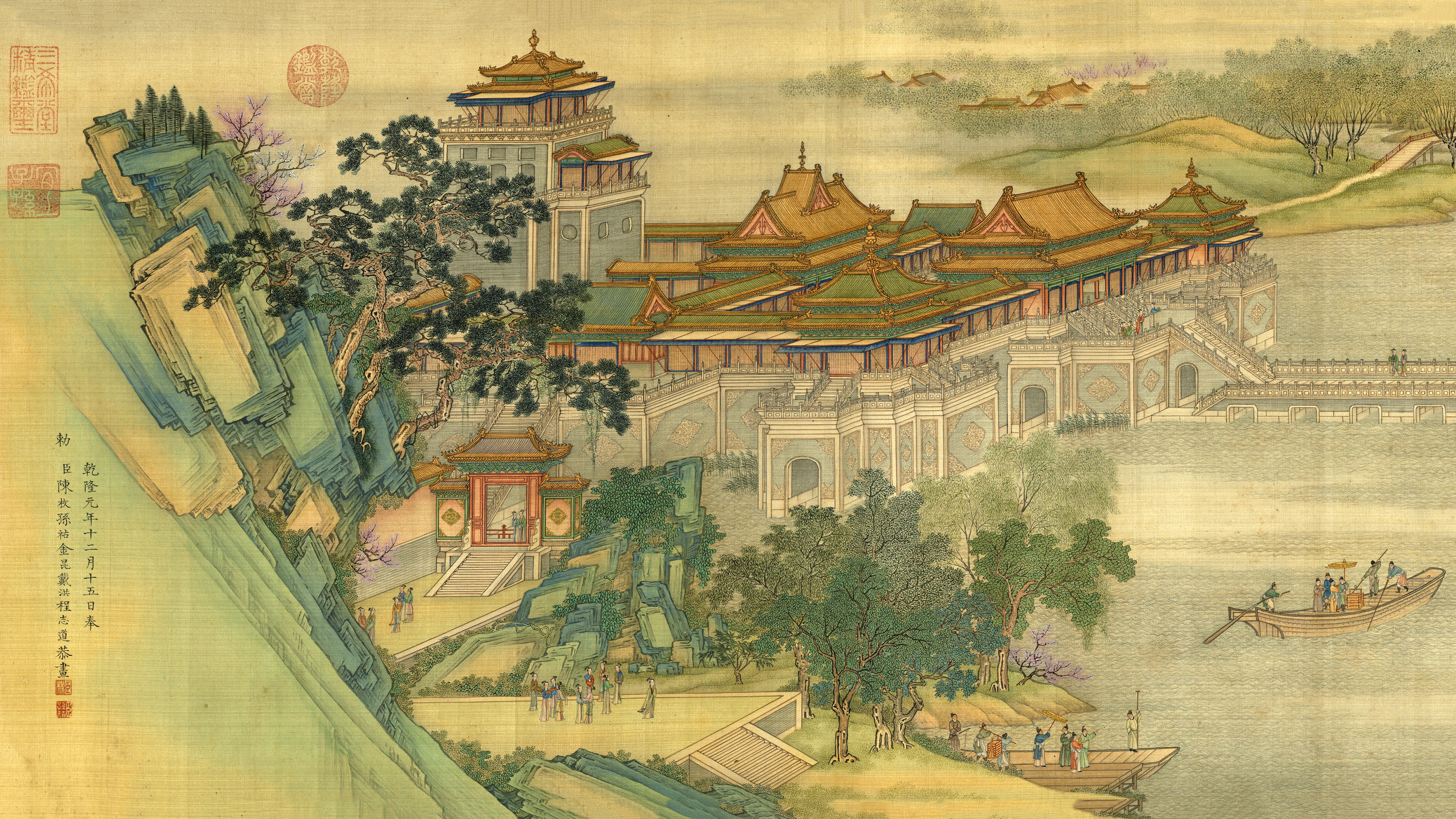

A small part of a 12h century scroll painting: Along the River, During Qingming (18th century reproduction)

A small part of a 12h century scroll painting: Along the River, During Qingming (18th century reproduction)